Laughter, Violence, and Takeshi Kitano’s Ultimate Genre Prank

A comedian, a Yakuza film legend, and a game show host walk into a bar. Spoiler alert: They’re all Takeshi Kitano.

My first encounter with Takeshi “Beat” Kitano was in the aughts, when I’d come home from school, turn on the TV, and watch Spike TV’s Most Extreme Elimination Challenge — a dubbed game show that repurposed all of the footage from the late-80s Japanese show Takeshi’s Castle. It was basically Wipeout before Wipeout even existed, but more ludicrous and much more hysterical. Eventually, this led me to seek out the original, where Kitano offers commentary while contestants get absolutely wrecked by obstacles more ridiculous than the last, all in an attempt to reach Kitano himself who is — you guessed it — in a castle.

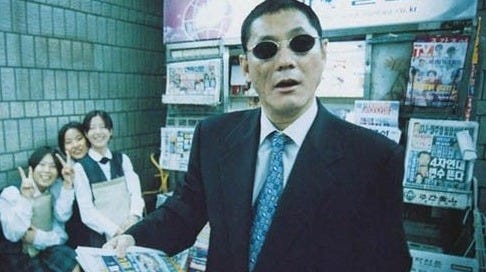

Around this time, Kinji Fukasaku’s Battle Royale (2000) was also put on my radar. I went into the film armed with the knowledge that it was just, well, cool (I had heard about Quentin Tarantino raving about it, which, at the time, was enough validation for me), and sure enough, I adored it. But what perhaps surprised me the most was seeing Kitano playing a terrifying yet cripplingly burnt-out high school teacher (if you haven’t seen the film, saying anything else would be a total disservice). Having only known about him thanks to Takeshi’s Castle, I was floored at his transformation into a chilling villain.

Beat Takeshi remained in my cinematic orbit for over a decade since, until a few years ago when I finally decided it was time to dive into his work as a filmmaker (he’s directed 20 films in total, as of this writing). Sonatine (1993) and Hana-bi (1997) are still my undeniable favorites, although my recent watch of his debut, Violent Cop (1989), may be encroaching on that pantheon. In any case, I mention all of this to you because I really think to get down ‘n’ dirty with his newest effort, Broken Rage, it would help greatly to be familiar with his style thus far — both as a comedian and too-cool-for-school crime film star. At the very least, if the flick isn’t for you, you’ll still walk away with a better understanding of what he’s doing (though to say anyone fully understands this audaciously self-reflective experiment… well, I’d wager only Kitano himself does).

Kitano is an artist whose career has thrived on contradiction. In fact, he even kind of stumbled into the entertainment business. Born on January 18th, 1947, he grew up the youngest of four children in the working-class district of Tokyo, his father a house painter and his mother a bean cake factory worker/ part-time toy manufacturer. Post-war Japan saw the Yakuza flourish. According to Kitano, in his neighborhood, “there were two types of people that were considered cool: professional baseball players and Yakuza.” Interestingly, it’s the latter that would roam young Takeshi’s neighborhood and who kept the kids straight. Straight he stayed, eventually deciding to study engineering at Meiji University — until he dropped out. Working a series of random jobs, he snagged a gig as a busboy at a strip club. One night, the owner was hosting a sketch comedy event, and when one of the performers backed out, he asked Kitano to sub in. That moment sparked something, and before long, Kitano’s career was on an unexpected trajectory.

Comedy was clearly in Kitano’s veins, so he began working under comedian Senzaburo Fukami as his apprentice. He later formed “The Two Beats,” a comedy duo consisting of Kitano and Kiyoshi Kaneko — aka Beat Takeshi and Beat Kiyoshi. The Two Beats were incredibly popular, even attracting the attention of various Yakuza members who would go watch them perform in nightclubs. As these mobsters would invite them to have drinks with them post-performance, they’d fill their heads with outlandish retellings. Little did Kitano know that those Yakuza war stories, combined with his comedic instincts, would shape his future as a filmmaker.

The Two Beats eventually marched to the rhythm of their separate drums in the early 1980s. Kitano quickly became one of Japan’s most successful TV comedians and, by the late ‘80s, took on hosting duties for the now-iconic Takeshi’s Castle.

It’s important to backtrack a bit here and note that in 1983, Kitano took on his first serious film role in Nagisa Oshima’s Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence. (Sidebar: Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence features one of my favorite Ryuichi Sakamoto compositions — he also stars in the film alongside none other than David Bowie.) The reason I mention this is because this was the first time Beat Takeshi attempted to make the transition from beloved comedian to “legit” actor. He was actually quite proud of his performance (or, as he tells it, it was “not bad at all”). Unfortunately, his comedic fame turned out to be a double-edged sword.

“One day, I snuck into a theater to see their reaction, and was quite surprised to find that the first scene where I appear, the whole audience suddenly burst into laughter, as if I had suddenly appeared on stage doing a routine! I was devastated by their reaction, because this character was supposed to be very intimidating and mysterious, not somebody to be laughed at!”

-Takeshi Kitano, via The Hollywood Interview

After Oshima’s film, Kitano spent the following decade taking on “dark” roles until the public realized there was nothing to laugh about. In fact, just six years later, he made his feature directorial debut with Violent Cop (1989), a film that left no room for laughter — unless, of course, Kitano decided otherwise.

Even within his filmography, Violent Cop stands out for its sheer brutality. The violence isn’t overly stylized or poetic: it’s raw, jagged, and unpredictable, only amplified by the restless handheld camerawork that keeps throwing itself at you. When the camera is static, the shots are agonizingly long — and usually with sparse dialogue. I can only imagine what audiences thought, walking into the theater expecting the beloved gagster, only to be met with this. With Violent Cop, Kitano wasn’t just shedding his comedic persona; he was planting the seeds for the stripped-down existentialism that would come to define his work.

Now, the film’s plot follows your usual crime tropes: a cop (played by Kitano himself) is well-respected at his station, but he’s known to have a violent temper (if you’ve seen the film, that’s a gross understatement, ha). While investigating the drug pushing activities of a local Yakuza, he discovers a colleague may be involved. Chaos ensues (or keeps ensuing, considering Kitano’s seen mercilessly pummelling someone every five minutes). Yet, what he does — and does so well — is casually weave in pockets of his signature, deadpan humor. Watching Kitano go about his business while an off-kilter rendition of “Gnossienne No. 1” plays is priceless, while the ways he cheekily rattles the rookie cop assigned to work with him will surely entice giggles.

Of course, Kitano’s style didn’t remain as raw and brutalistic as Violent Cop. As the years passed, his films took on a more introspective rhythm, such as the dance between violence and melancholy in Sonatine (1993). Hana-bi (1997) was equally, if not more, poetic — which makes sense, considering what a personal film it was for Kitano. Just a few years prior, he survived a near-fatal motorcycle accident that left him with partial facial paralysis. With Hana-bi, he refined his balance of extreme violence and quiet, painterly poeticism. In fact, we see Kitano’s character paint on-screen, mirroring his own turn to painting as a form of therapy after the crash.

While Hana-bi and Sonatine refined Kitano’s signature blend of deadpan stillness and sudden brutality, his Outrage trilogy (beginning in 2010) took a more direct, unrelenting approach. These films were cold, methodical, and bleak.

And now, my (very) patient reader, all of this brings us to Broken Rage: a film that, decades later, feels like Kitano placing a giant bow on his entire oeuvre.

It’ll be hard to talk about Broken Rage without spoiling it, although any tiny synopsis online does just the same. In just 66 minutes, Kitano (who also wrote the script and stars in the film) splits the runtime into two contrasting segments. In the first, the thriller is played straight, following all the tropes we’d come to expect from the gangster genre. The filmmaker plays Mouse, an aging hitman who receives mysterious envelope-enclosed contracts at the same cafe. Naturally, Kitano is still just as unbothered as he was decades ago, delivering the slickest, reflex-like killing abilities. The one time he gets a bit lazy, however, he’s apprehended, suddenly having to work with the cops to take down a local Yakuza kingpin for his freedom. While I won’t say how this story plays out or concludes, it doesn’t take long to end. Suddenly, Kitano turns back the clock, delivering what appears to be the same tale but with overt, slapstick comedy. The opening drone shot of Tokyo doesn’t glide with ease anymore — it comes crashing to the ground. Mouse can’t sit on a chair without it breaking, nor is he exactly subtle about his assassinations. Truth be told, I’m surprised there wasn’t a single banana peel slip; if it happened, I wouldn’t have batted an eye.

To go any further and spoil any other gags would be just plain rude, as Kitano basically set up a joke for every scene in the first iteration of the tale. So ridiculous it is, in fact, that there are scenes where we see actors visibly breaking and stifling back giggles. Another sidebar: There are some incredible stars here — the two cops are played by Nao Omori (Ichi himself, from Ichi the Killer) and Tadanobu Asano (of Shogun fame). To see them, alongside Kitano, look like they’re having the time of their lives is a joy in itself. Broken Rage is the sort of film I urge you to host a watch party for, preferably with fans just as psyched about Kitano releasing a new film as I am.

While Kitano is parodying the first half of the film with the second, the first in itself is also a spoof. The plot still managed to keep me invested, but it’s a clear nod to Kitano’s detached-but-cool gangster-centric filmography. If it felt familiar, it was supposed to. And right before you sit there, thinking, “Well, why isn’t Kitano doing anything new?,” he pulls the rug from under you, delivering something so wholly unique, but, yet again, sees him tapdancing (or, more accurately, falling) back to the genre that catapulted him into fame in the first place.

Sure, Broken Rage isn’t Kitano’s best effort — far from it. But you know what? He’s almost 80 and still having a riot. And I love that. In fact, even before the release of Broken Rage, Kitano decided to climb back into his castle for a reboot of his beloved and utterly bananas game show.

Whether Broken Rage is a farewell or just Kitano having some fun, it feels like the perfect encapsulation of his career: one that he crafted entirely on his own terms. Like I said, Kitano has always thrived on contradiction, and Broken Rage is just another electric example of that push-and-pull. He once told Mubi’s Notebook, “Laughter has a rather devilish side to it.” That rings true with whatever he does. After all, King Takeshi always gets the last laugh.

https://youtu.be/lo4B-pJDrlc?si=V13aDscnx_p2fb2K

Very well written article and a joy to read! I'm a big Kitano fan (my fav is probably Boiling Point, but I'm not yet a completist). I've been putting off watching Broken Rage out of worry that it will be kinda embarrassing, but you're framing of it in terms of his career arc has me way more excited. I was gonna watch it eventually! I also remember Most Extreme Elimination Challenge through a kind of hazy nostalgic fugue state haha