Taste of Cherry: The Weight of a Mulberry and the Poetry of the Ordinary

A meditation on solitude, silence, and the beauty found in the everyday in Abbas Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry.

CW: This piece discusses themes of death by suicide, which may be distressing for some readers.

Please take care while reading.

Nourishment for the soul; replenishment for the spirit — that’s how I would describe Abbas Kiarostami’s work.

I began my journey through his filmography later than I’d like to admit — February 2023, to be exact — beginning with Where Is the Friend’s House?, only to realize it was the first part of his Koker Trilogy, alongside Life, and Nothing More… and Through the Olive Trees. From the start, I was drawn to his ability to craft gentle, incredibly human stories, effortlessly blending fiction and reality. Despite the heavy themes he often explores, there’s an undeniable comfort in his films: A quiet reassurance that I am not alone.

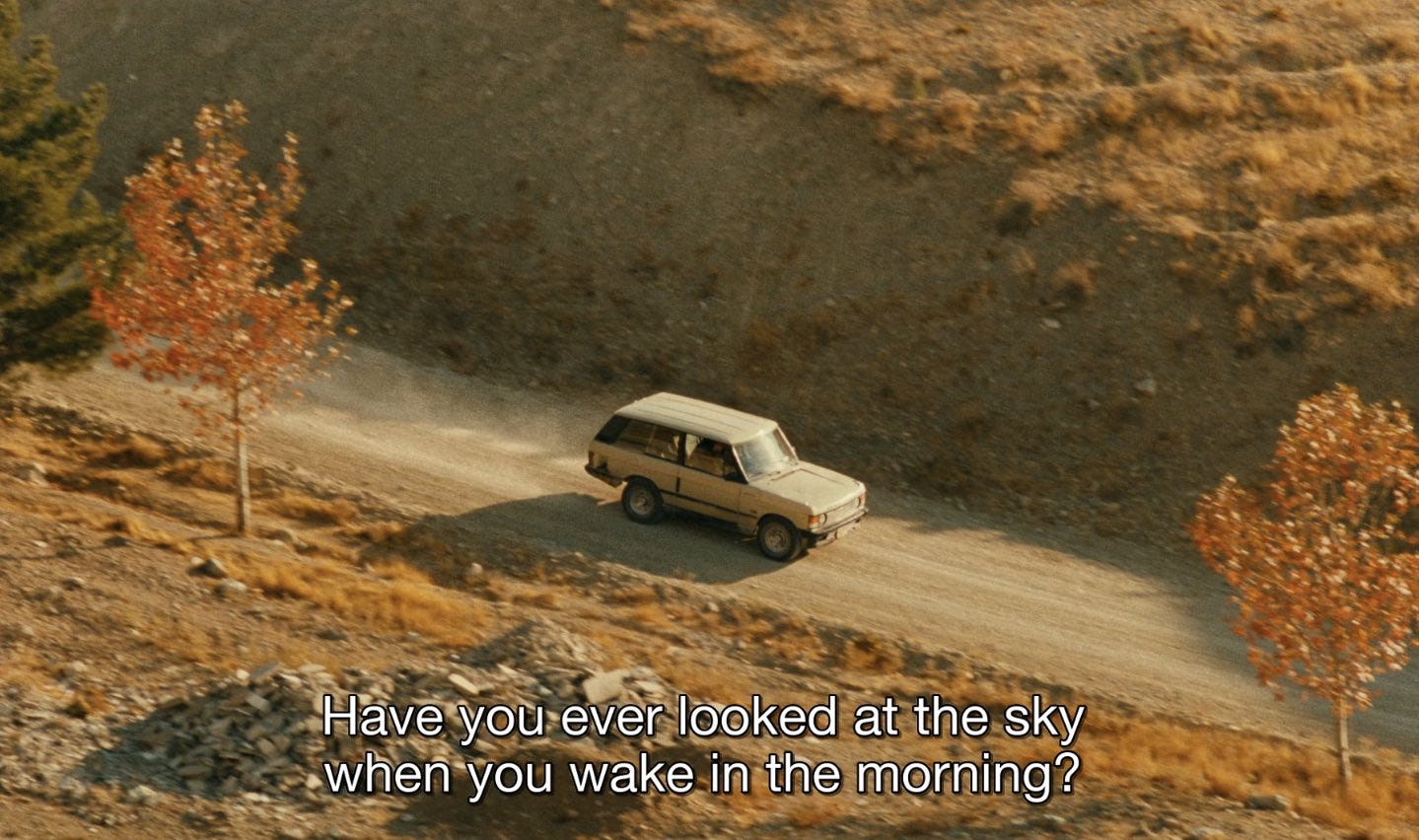

Kiarostami captured life in simple, fleeting moments. Sunlight moving across a hillside scattered with trees, the unhurried rhythm of a conversation between strangers, the beauty hidden in the mundane. Whenever I feel overwhelmed, his films envelop me in their warmth, reminding me to pause. To notice. To see.

Taste of Cherry (1997), perhaps more than any of his other films, embodies this philosophy in its starkest, most profound terms. There’s a strange beauty in sitting with uncertainty, in surrendering to solitude. When you do, your senses sharpen. It’s an invitation to see the world anew.

Recently, I had the pleasure of exploring these very ideas in conversation on The Substance Podcast, hosted by Philip Marinello (I’ll link the episode at the bottom of this article). Given the chance to revisit Taste of Cherry in such depth, I knew this was the perfect excuse to reflect on one of my all-time favorite filmmakers and a movie that continues to resonate with me in ways I will try my best to articulate.

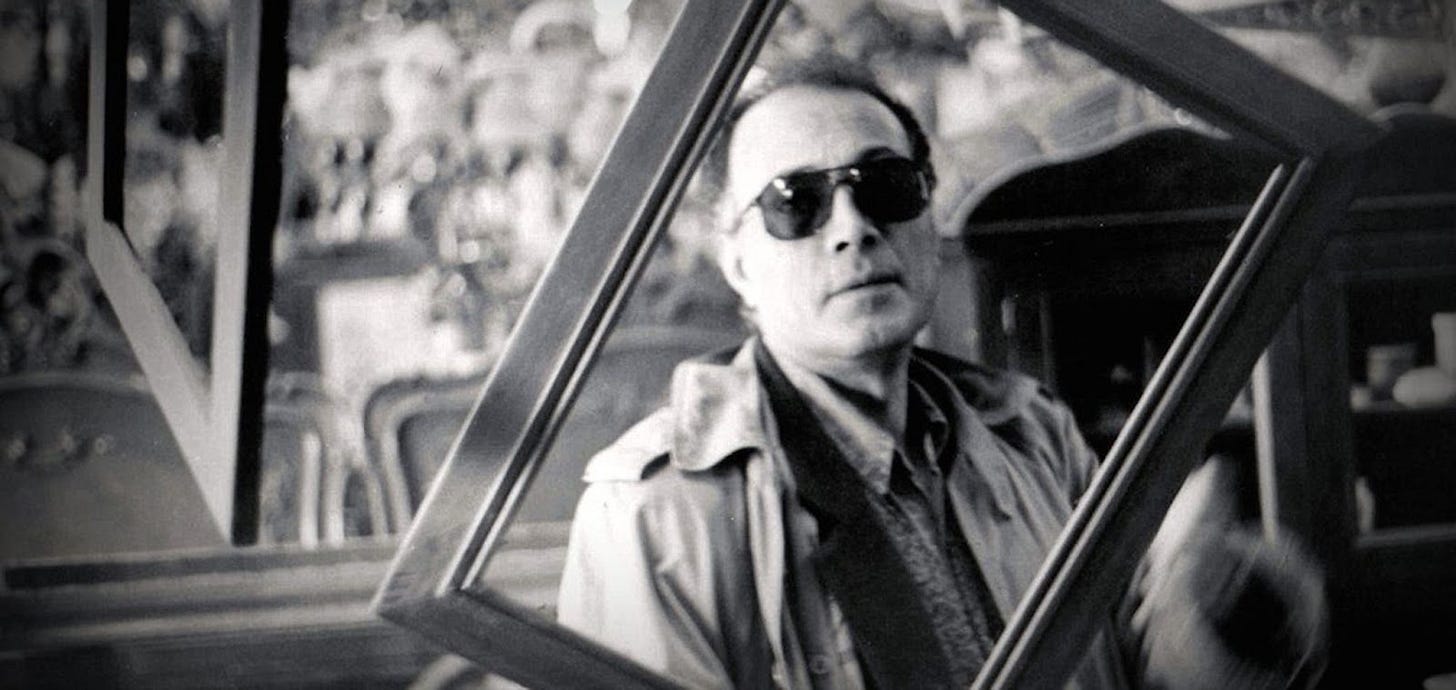

Abbas Kiarostami was born in Tehran, Iran, on June 22, 1940. While still young, he developed an interest in painting — his first passion before film. This early artistic foundation explains his stunning cinematic language: the way landscapes become living, breathing canvases within his frames. At 18, after flunking out of his university’s fine arts program, Kiarostami took a job as a traffic cop, which allowed him to enroll in another art school simultaneously. From there, he worked as a commercial artist, designing book covers, posters, and eventually TV commercials. Nearing his thirties, he was tapped to establish the film sector for Kanun — the Institute for Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults.

The goal of this sector was to produce educational films. The ones that taught a lesson. This influence carried throughout his career, as Kiarostami consistently challenged his audiences to become active participants, engaging with his films beyond what was presented on screen. Mahmoud Reza Sani’s Cinematic Lessons from Abbas Kiarostami (which I highly recommend picking up for a quick read) captures this idea perfectly, opening with a quote from the filmmaker himself: “Art doesn’t make judgment; what art does is make you think.”

As I mentioned, Kiarostami was a master at documentary-style realism (most notably with 1990’s Close-Up — a film I love dearly). His characters are often on a kind of quest, asking questions about where they are and where they want to go. This gentle, philosophical approach naturally unfolds into existential reflections on life itself.

Then, of course, there are the cars. I can’t tell you the joy I feel when I see a Kiarostami character enter a vehicle — you just know you’re about to get some thought-provoking heat. His protagonists often tap passersby for directions or information, but what begins as a simple exchange inevitably blossoms into something deeper. These journeys bring comfort in their quiet revelations and reflections on human resilience. How undeniably beautiful that is, no?

I often say that I leave a Kiarostami film feeling the same way I do after watching something by Yasujirō Ozu: calmer, more attuned to life’s small wonders. With that statement comes a fascinating fact: While Kiarostami never considered himself a true “cinephile,” he wholly respected the Japanese auteur. In fact, he even made a documentary dedicated to Ozu in 2003, Five. Speaking about his work, Kiarostami once reflected, “Ozu’s cinema is a kindly cinema. He values interactions, natural relationships, the natural human in all of his films.”

Kiarostami’s genuine appreciation for life’s small moments feels much more profound when you consider it against the backdrop of the Iranian Revolution. The fall of the Shah in 1979 ushered in sweeping cultural and political changes, fundamentally reshaping Iran’s artistic landscape. While his earlier films often portrayed Tehran as a place of modernity and corruption, his post-revolution work saw characters seeking refuge beyond the city, searching for meaning in rural villages and nature.

Direct political critique was risky, but Kiarostami found ways to explore weighty themes of morality and resilience through allegory, urging viewers to look beyond the surface. In Where Is the Friend’s House?, for instance, a child’s determination to return his classmate’s notebook becomes a quietly radical act, presenting broader questions of ethical responsibility. With Taste of Cherry, this shift is even more deeply felt. Here, silence and unanswered questions become just as vital as the dialogue itself.

Taste of Cherry, which won Kiarostami the Palm D’or, is a deceptively simple film. We follow Mr. Badii (Homayoun Ershadi), a man driving through the outskirts of Tehran, searching for someone to help him die by suicide. His request isn’t for a violent act but something more detached: He has dug a hole in a remote area, where he plans to take an excess of sleeping pills that evening. His chosen participant will arrive the following day, throw two stones into the pit, and — if Badii responds — help him out. If not, they are to bury him. For this task, he offers a vast sum of money.

Over the course of the film, Badii approaches three different men: a young soldier, an Afghani religious student, and an elderly Turkish taxidermist who works in a wildlife museum. Through these interactions, we begin to understand Badii’s predicament, not through explicit reasoning, but through absence and suggestion.

In an interview with Jonathan Rosenbaum, published in Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia, Kiarostami offered a rare insight:

“He doesn’t pick up a couple of workers at the beginning who would be willing to kill him with their spades; he chooses other people whom he probably thinks he can have a conversation with. So that gives us a signal that he’s probably not searching for someone who would help him to kill himself.”

Mr. Badii is painfully lonely. He may not express it outright, but Kiarostami does — through striking visual language. Taste of Cherry unfolds almost entirely in exteriors… yet Badii is perpetually confined to his car. A personal isolation. A floating coffin en route to its final resting place.

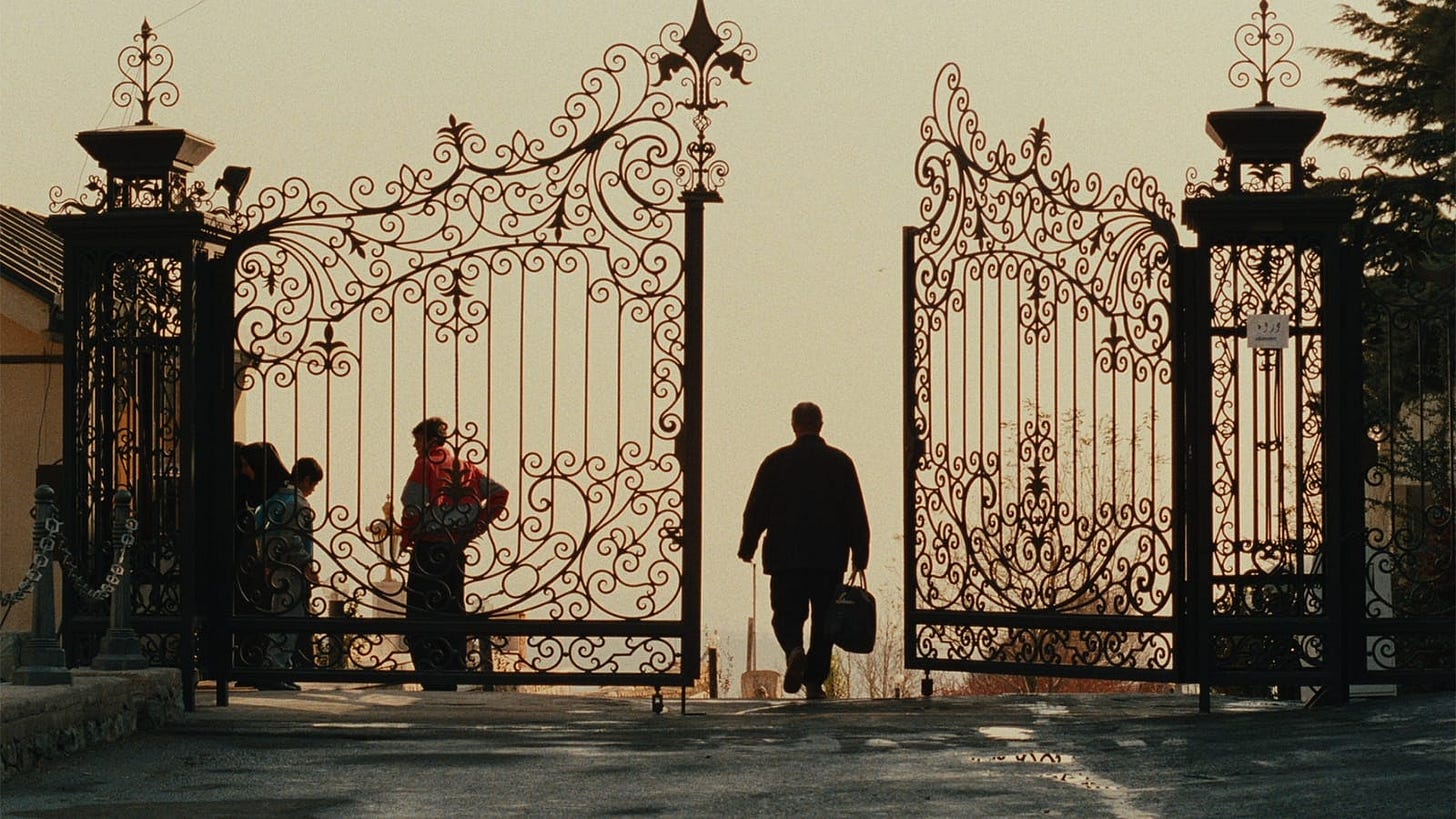

Through Badii’s journey, small, gentle nudges begin to awaken him to the beauty of the mundane. Pockets of poetic warmth are scattered throughout Taste of Cherry: birds soaring past a pink sky, a group of locals banding together to help him when his car gets stuck; not for money, but out of an unspoken sense of community. However, the most beautiful moment comes in Badii’s exchange with the taxidermist.

After Badii reveals his daunting request, the man confesses that there was a time when he, too, couldn't go on. He had planned to end his life beneath a mulberry tree. But before doing so, he decided to taste a mulberry… and then another. And as he looked around, something shifted. The world that once felt distant suddenly revealed itself in small, quiet details. “A mulberry saved my life,” he tells Badii, only to later plead, “Do you want to give up the taste of cherries?”

I’m getting shivers at that final quote. The scene I just described is what makes Taste of Cherry so haunting. It doesn’t offer us any easy answers; only an invitation to sit with its silences. The ultimate test comes at the film’s end, though that’s something I wouldn’t dare spoil for those of you who have yet to watch it. Perhaps Kiarostami’s goal was to leave us in our own isolation. To sit and truly appreciate the beauty of life. It’s a gift, this space he leaves us with.

In a 1995 speech in Paris, Kiarostami articulated this very philosophy:

"It is a fact that films without a story are not very popular with audiences, yet a story also requires gaps, empty spaces like in a crossword puzzle, voids that it is up to the audience to fill in … I believe in a type of cinema that gives greater possibilities and time to its audience. A half-created cinema, an unfinished cinema that attains completion through the creative spirit of the audience."

Allow Taste of Cherry to linger. Allow it to expand; to transform long after you walk away from Badii’s story. Remember the weight of a mulberry and the poetry of the ordinary.

If you want a deeper dive into Taste of Cherry, I urge you to head over and listen to my discussion with Philip Marinello on The Substance Podcast. The Substance is a semi-weekly podcast (about three shows a month, with one week off) with well over 150 episodes that has conversations to help folks better appreciate goodness, truth, and beauty. There’s a strong emphasis on cinema, with regular conversations with wonderful guests who work in the film world. As well as shows with academics, advocates, and faith leaders who are working to make the world a better and fuller place.

I watched it this morning. Been thinking about life a lot lately, gonna be sitting on this one for a while I think