The 10th Victim: Elio Petri’s Pop-Art Dystopia

High camp, high fashion, and a compromised vision of consumerist dystopia — Elio Petri’s 1965 cult classic is more than just pulp.

Elio Petri’s The 10th Victim (1965) is a glam, mod, bullet-bra’d vision of dystopia — and one that’s far more loaded than its high-camp surface suggests. Violence becomes spectacle, death a televised game, and romance just another scripted performance. But what happens when a fiercely political filmmaker is forced to coat his critique in high-fashion and commedia all’italiana? You get a wild contradiction: something flashy, compromised, and simultaneously gripping.

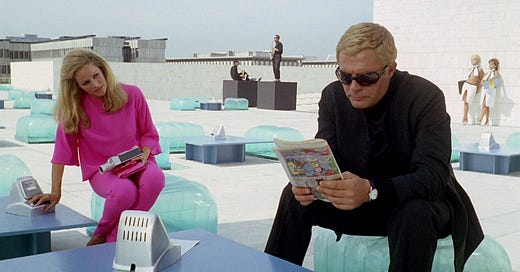

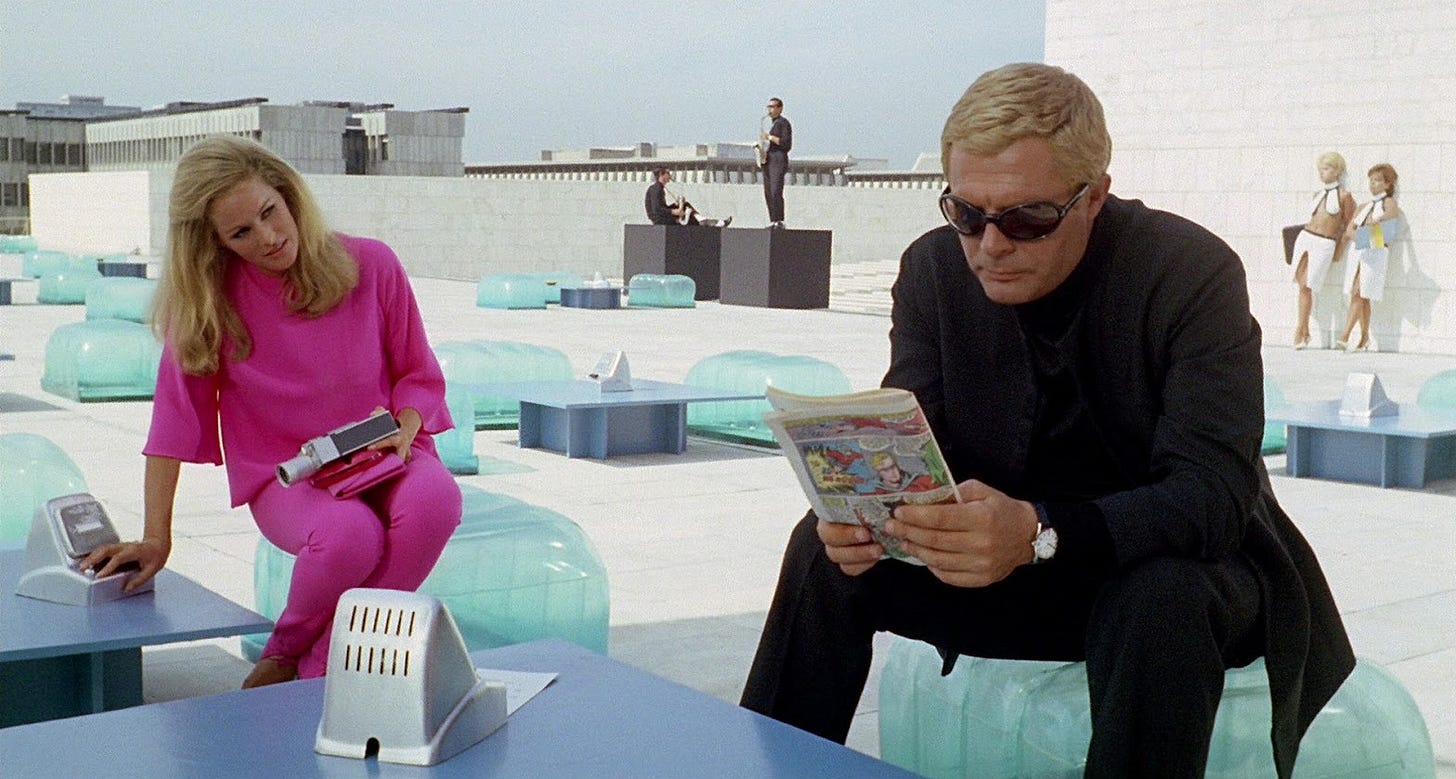

Set in a dystopian future where legalized murder is televised entertainment, the film follows a government-endorsed game called The Big Hunt. Contestants alternate between being hunter and victim, rewarded with fame and fortune the longer they survive. What makes this especially dicey for the victim is that the hunter knows everything about them, while the victim is left in the dark. When champion killer Caroline Meredith (Ursula Andress) is assigned her tenth and final target — Marcello Poletti (Marcello Mastroianni), an Italian who may or may not be onto her — we’re gifted witness to a seductive and deadly showdown.

The 10th Victim was remarkably ahead of its time, predating a slew of films that tackle violence and death as spectacle (think: The Running Man, Battle Royale, The Hunger Games, and beyond). The idea for the movie, based on Robert Sheckley's 1953 short story Seventh Victim, was one that hooked Petri. A filmmaker never one to shy away from controversial or political themes, Sheckley’s story aligned perfectly with the kind of science fiction Petri gravitated toward. As he said in a 1962 interview with Cinema Domani:

“Science fiction is an ironic mirror of our fears towards the future, and in this sense, unfortunately, it has a rather extensive realistic basis. We see many aberrations around us, and unleash our fear for what might happen next by way of elegant, albeit horrendous, hypotheses. Through science fiction we paint a psychic picture of our times, and our pessimism is patent: I have never read a science fiction story which gave a portrait of a future devoid of fear and rooted in hope.”

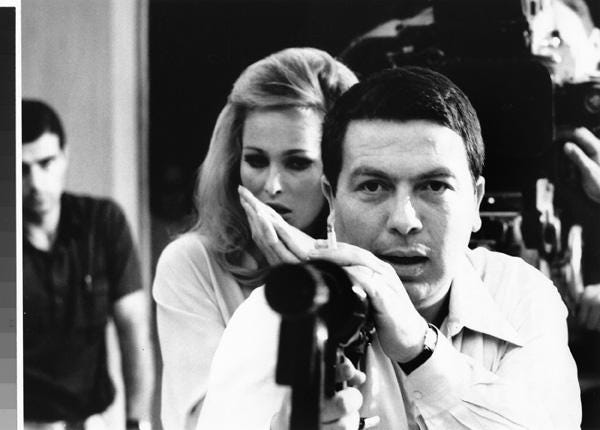

Petri’s filmography has always been steeped in social critique. Before The 10th Victim, he cut his teeth working alongside filmmaker Giuseppe De Santis and was deeply embedded in leftist political thought. He would go on to direct some of the fiercest films I’ve seen from Italy’s postwar cinema — from Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (his most well-known and 1971 Academy Award winner for Best Foreign Film) to The Working Class Goes to Heaven (my favorite and winner of the 25th Cannes Film Festival, shared with with Francesco Rosi's The Mattei Affair) — consistently examining power, labor, and the individual’s place within the system. In his own words, his stories were “of individuals — and the overall conditioning they find themselves — without losing sight of the social and historical events and their class essence as exterior conditioning factors.”

Although far from a perfect film, that sensibility permeates The 10th Victim — even when the film is at its most playful. What’s interesting here is that originally, Petri’s script was much more dystopian and pessimistic. Love hadn’t existed for 200 years, reproduction was entirely artificial, and the elderly (deemed “useless” to society) were placed in cruel, institutionalized spaces that left them regressing to childlike states. Satirical elements were even sharper, such as Big Hunt contestants shopping at dedicated supermarkets for their weapons and gadgets of choice. The ending, too, was much darker — though I don’t want to spoil it here, as doing so would give away the one that ultimately made it to screen. What Petri had was a clear vision: a scathing future ruled by consumerism, alienation, and spectacle. So, what happened?

The budget for The 10th Victim was, understandably, colossal. So, who does one tap when working in the Italian film industry at the time? Carlo Ponti: one of its biggest heavyweights. The catch? The producer had zero interest in sci-fi, nor did he particularly care to work with Petri. However, the filmmaker had one ace up his sleeve: Marcello Mastroianni, a major box office draw. Ponti was on board… on one condition. The script would be rewritten by other writers (to varying degrees, some even without credit) to make it more palatable for the American market. Petri agreed, but not without consequence.

“I worked on the script for a year and a half and arrived exhausted at the end, always with Ponti putting sticks in the wheel.”

The final result was far from what Petri had envisioned. Even before the film’s release, he preemptively framed expectations, telling the press, “A film must be made for an audience so we’re coating the pill considerably. The surface action and all that should please the spectator. Then if he wants to dig below the surface, so much the better.”

Yet, with all of Petri’s frustrations, The 10th Victim still manages to be a blast, albeit one that could have used more meat and potatoes. As it stands, it’s a tantalizing dessert laced with arsenic. Stylish, slick, and overflowing with visual pleasures — from its stunning costume design to its wildly creative concepts like the bullet bra (later paid homage to in Austin Powers). Your eyes will be glued to the screen.

Of course, Mastroianni is always a delight to watch, as is Ursula Andress (at the top of her game at the time, fresh off playing Honey Ryder in 1962’s Dr. No), who weaponizes her sexuality and flips the power dynamic in a way that’s both playful and pointed.

Although the film clearly pulled back from the sharper satire of what once was, Petri still managed to sneak in some barbs. If you thought that the central romance felt hollow, guess what? The point was to make it feel performative and transactional in this future world. Even the production design — as modernist and hyper-staged as it is — mirrors the society it depicts: elegant, yet incredibly empty. This is Boss Level Capitalism, baby, and we’re all performing since morality has no merit.

With so much that it predates cinematically, Petri also delivers passing jokes that are chillingly prescient, like when Caroline shrugs and notes, “In America, there aren’t many restrictions for hunters. Everyone can easily shoot wherever and whenever they want to.”

I can’t talk about The 10th Victim without addressing the elephant in the room: the ending. It’s what holds me back from rating the film higher (my Letterboxd score sits at a 4/5). The 10th Victim wraps up with a tidy bow that obviously wasn’t Petri’s choice. You can only guess who we have to blame: Ponti. Again. He reportedly fought tooth and nail for something darker, more cynical, only to find himself worn down:

“If only you knew how much I sweated to convince the producer, and how much I suffered to adapt myself to that horrible clownish ending … But I couldn’t handle it anymore, having to fight against everyone.”

Beneath the film’s bouncy score and elaborate set pieces lies a work built on tension, not just within the story but within the very process of its creation. Yet, even with all the compromises, The 10th Victim still manages to hold a mirror up to our distraction-addicted world, where feasting on the media machine only feeds into our worst instincts. Eerily familiar, no?

Holy shit...Austin Powers stole this for the fembots 🤣